Table of Contents

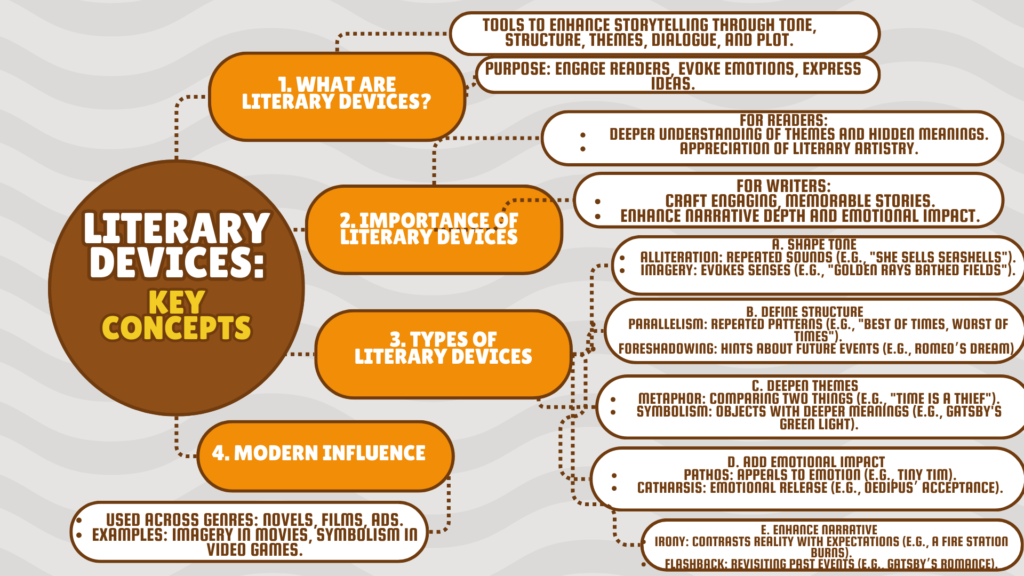

- What Are Literary Devices?

- Why Should You Learn Literary Devices?

- Functions of Literary Devices

- Types of Literary Devices

- Cultural Influence and Modern Adaptations

- FAQs: Literary Devices Explained

Literary devices are essential tools in storytelling. They help writers express ideas, evoke emotions, and keep readers engaged. Understanding these devices allows readers to appreciate the artistry behind literature. This guide provides clear definitions, detailed examples, and insights into why each literary device matters.

What Are Literary Devices?

Literary devices are techniques that shape how a story is written and received. They can influence tone, structure, themes, dialogue, and plot complexity, enhancing both the writer’s craft and the reader’s experience. Literary techniques are used across various forms of writing, from novels to films and even advertisements, allowing creators to evoke emotions, convey messages, and engage their audience more effectively.

Why Should You Learn Literary Devices?

Understanding literary devices benefits readers and writers by enriching their interaction with literature. Here’s how:

- For Readers:

- Deeper Analysis: Literary devices help readers uncover hidden meanings, themes, and underlying text messages.

- Enhanced Appreciation: Recognizing a writer’s techniques allows readers to admire the complexity and artistry of literary works.

- For Writers:

- Engaging Narratives: Writers use literary devices to create vivid imagery, memorable characters, and emotionally impactful stories.

- Refined Craftsmanship: Mastering these tools improves a writer’s style, making their work more captivating and resonant.

- For Both:

- Timeless Connection: Literary devices form the backbone of stories that resonate across cultures and generations, fostering a universal appreciation of literature.

What Are the Functions of Literary Devices?

Literary devices serve as universal artistic frameworks, enhancing the depth and meaning of a text. Writers employ these tools to create logical structures and enrich their works with layered significance. Their functions include:

- Enhancing Aesthetics: Literary devices beautify a text, making it more enjoyable and thought-provoking for readers.

- Encouraging Analysis: They challenge readers to interpret complex ideas and themes, deepening their understanding.

- Stimulating Imagination: By painting vivid pictures of characters and scenes, these techniques ignite the reader’s creativity.

- Fostering Comparison: Because of their universality, literary devices allow readers to evaluate and compare works from different authors or cultures, measuring their artistic merit.

By combining artistry with function, literary devices bridge the gap between writers and readers, creating meaningful and impactful works.

Types of Literary Devices: Categories and Examples

Literary devices are divided into several categories, each serving a unique purpose in literature. These devices contribute to the tone, structure, narrative depth, and thematic exploration in a text. Let’s explore these categories with detailed examples.

I. Literary Devices That Shape Tone

Tone sets the emotional quality or mood of a text. The following literary devices are key to establishing tone:

1. Alliteration

- Definition: The repetition of initial consonant sounds in closely placed words to create rhythm or emphasis.

- Examples:

- “She sells seashells by the seashore” uses repeated “s” sounds to create a lyrical and musical effect.

- Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven: “Doubting, dreaming dreams no mortal ever dared to dream before.” Here, the repetition of the “d” sound reinforces the narrator’s introspection and unease.

- Purpose: Alliteration enhances the rhythm of the text, making passages more memorable and engaging. It can also intensify the mood, creating a soothing or ominous tone depending on the context.

2. Hyperbole

- Definition: Deliberate exaggeration used for emphasis or dramatic effect.

- Examples:

- “I’m so hungry I could eat a horse” conveys extreme hunger humorously.

- J.D. Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye: Holden’s statement, “It rained like a bastard,” exaggerates the intensity of the rain to mirror his frustration and gloomy state of mind.

- Purpose: Hyperbole emphasizes strong emotions, drawing readers’ attention to a character’s feelings or the story’s dramatic moments. It can add humour or evoke sympathy, depending on its application.

3. Imagery

- Definition: Descriptive language that appeals to the senses (sight, sound, touch, taste, smell) to create vivid mental images.

- Examples:

- “The golden rays of the sun bathed the lush, green fields” appeals to sight, evoking tranquillity.

- John Keats’ Ode to a Nightingale: “Fast fading violets covered up in leaves” evokes a melancholic yet beautiful scene, reflecting themes of transience and loss.

- Purpose: Imagery immerses readers in the narrative, making scenes and emotions more vivid and relatable. It shapes tone by amplifying the atmosphere of the text.

II. Literary Devices That Define Structure

Structure shapes how a story unfolds. These devices influence the organization and flow of the narrative.

1. Parallelism

- Definition: The repetition of similar grammatical structures for emphasis and rhythm.

- Examples:

- Martin Luther King Jr.’s “I Have a Dream” speech: “I have a dream that one day… I have a dream that one day…” uses repetition to underline hope and equality.

- Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” This juxtaposition prepares readers for the duality of the novel’s themes.

- Purpose: Parallelism enhances readability, creates balance, and reinforces key ideas, making them more impactful.

2. Foreshadowing

- Definition: Subtle hints or clues about events that will occur later in the narrative.

- Examples:

- John Steinbeck’s Of Mice and Men: The shooting of Candy’s dog foreshadows Lennie’s fate, symbolizing themes of mercy and inevitability.

- Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet: Romeo’s line “My mind misgives some consequence yet hanging in the stars” anticipates the tragedy to come.

- Purpose: Foreshadowing builds anticipation, creating suspense and preparing readers for significant plot developments.

3. Repetition

- Definition: The deliberate use of the same word or phrase multiple times to emphasize an idea.

- Examples:

- Winston Churchill’s wartime speech: “We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds…” repeats “we shall fight” to inspire resilience and unity.

- Edgar Allan Poe’s The Raven: The word “Nevermore” is repeated, symbolizing the narrator’s unending despair.

- Purpose: Repetition reinforces key themes or emotions, ensuring they resonate deeply with readers.

III. Literary Devices That Enhance Narrative

Narrative devices drive the story forward by adding complexity, depth, and meaning.

1. Allegory

- Definition: A story in which characters, settings, and events symbolically represent broader concepts or moral lessons.

- Examples:

- Plato’s Allegory of the Cave: The cave represents ignorance, while the journey to the surface symbolizes enlightenment.

- George Orwell’s Animal Farm: The animals represent societal classes and political ideologies, critiquing authoritarian regimes.

- Purpose: Allegories simplify complex ideas, making philosophical or moral concepts accessible to readers.

2. Symbolism

- Definition: The use of symbols (objects, characters, or actions) to represent abstract ideas or themes.

- Examples:

- F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby: The green light represents Gatsby’s aspirations and the illusory nature of the American Dream.

- William Golding’s Lord of the Flies: The conch shell signifies order and civilization, while its destruction marks the descent into savagery.

- Purpose: Symbolism adds layers of meaning, encouraging readers to interpret and engage more deeply with the text.

3. Irony

- Definition: A discrepancy between expectation and reality, often highlighting contrasts or creating humour.

- Examples of Types:

I. Dramatic Irony

Definition: Dramatic irony occurs when the audience or reader knows something that the characters do not. This discrepancy between the character’s understanding and the audience’s knowledge creates tension or poignancy.

Example: In Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet, the audience knows that Juliet is not dead, but Romeo believes she is. This creates tragic irony as Romeo takes his own life, thinking Juliet is gone, while she is alive, leading to the tragic ending.

II. Situational Irony

Definition: Situational irony happens when there is a stark contrast between what is expected to happen and what occurs. It often surprises or shocks the audience.

Example: A fire station burning down is an example of situational irony. The expectation is that a fire station, where firefighters work, would be the last place to catch fire. The irony arises because the event contradicts the purpose and function of the fire station.

III. Verbal Irony

Definition: Verbal irony occurs when a speaker says something but means the opposite, often sarcastically or humorously.

Example: Saying “What great weather!” during a storm is an example of verbal irony. The speaker is referring to the bad weather, but the words they use suggest the opposite, highlighting the contrast between the literal meaning and the intended meaning.

- Purpose: Irony introduces humor, tension, or poignancy, while also emphasizing contrasts and complexities in the narrative.

IV. Literary Devices That Deepen Themes

Literary devices in this category help to communicate underlying ideas and messages within a work. They enable writers to convey abstract concepts in a way that resonates with readers.

1. Metaphor

- Definition: A direct comparison between two unlike things, where one is said to be the other, without using “like” or “as.”

- Examples:

- “Time is a thief”: This metaphor suggests that time robs people of their cherished moments, just as a thief takes possessions.

- Shakespeare’s As You Like It: “All the world’s a stage, and all the men and women merely players.” This metaphor equates life to a theatrical performance, where individuals play different roles.

- Purpose: Metaphors make abstract or complex ideas more tangible and relatable. They allow writers to create vivid imagery, encouraging readers to think deeply about the connections between seemingly unrelated concepts.

2. Juxtaposition

- Definition: Placing two contrasting ideas, characters, or situations close together to highlight their differences.

- Examples:

- Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities: “It was the best of times, it was the worst of times.” This juxtaposition highlights the dualities of hope and despair, wealth and poverty during the French Revolution.

- In Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, the monster’s innocence and longing for companionship are starkly contrasted with his violent actions. This creates tension and underscores the moral complexities of creation and rejection.

- Purpose: Juxtaposition emphasizes contrasts to develop themes such as conflict, morality, and the duality of human nature. It adds depth to the storytelling and provokes thought.

3. Motif

- Definition: A recurring element, such as an image, symbol, or idea, that reinforces the themes of a narrative.

- Examples:

- Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness: The recurring motif of darkness symbolizes ignorance, evil, and the unknown.

- Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird: The mockingbird motif represents innocence and the moral imperative to protect the vulnerable.

- Purpose: Motifs weave consistency into a story, helping readers identify and reflect on central themes. By recurring throughout the work, motifs create cohesion and add layers of meaning.

V. Literary Devices That Enhance Dialogue and Characterization

These tools are essential for crafting realistic dialogue and multi-dimensional characters.

1. Colloquialism

- Definition: Informal language, slang, or regional expressions used to reflect the culture or background of characters.

- Examples:

- Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn: “We said there wasn’t no home like a raft.” This colloquialism captures the dialect and attitude of the Mississippi River region.

- Purpose: Colloquialisms add authenticity to dialogue, making characters more relatable and vivid. They also provide insights into the social and cultural settings of a story.

2. Dialect

- Definition: Speech patterns that reflect a character’s geographic or social background.

- Examples:

- Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird: “Reckon I have. Almost died the first year I came to school.” Scout’s dialect conveys her Southern roots and youthful perspective.

- Purpose: Dialects ground characters in specific regions or communities, creating a more immersive reading experience. They can also highlight cultural diversity or class distinctions.

3. Soliloquy

- Definition: A speech where a character reveals their inner thoughts and feelings, often while alone on stage.

- Examples:

- Shakespeare’s Hamlet: “To be, or not to be: that is the question.” This soliloquy explores Hamlet’s existential crisis and internal conflict.

- Purpose: Soliloquies provide insight into a character’s motivations, emotions, and thought processes. They create an intimate connection between the character and the audience.

VI. Devices That Create Emotional Impact

These literary devices are designed to evoke strong feelings, leaving a lasting impression on readers.

1. Pathos

- Definition: A technique used to appeal to the audience’s emotions, such as pity, sorrow, or joy.

- Examples:

- Charles Dickens’s A Christmas Carol: Tiny Tim’s frailty and cheerful spirit elicit empathy and compassion.

- In Shakespeare’s Othello, Desdemona’s tragic fate evokes profound sorrow.

- Purpose: Pathos fosters an emotional connection, allowing readers to empathize with characters and engage more deeply with the story.

2. Catharsis

- Definition: The emotional release or relief experienced by the audience after the resolution of a dramatic conflict.

- Examples:

- Sophocles’ Oedipus Rex: The tragic downfall of Oedipus and his ultimate acceptance of fate provide catharsis for the audience.

- In Shakespeare’s Macbeth, the resolution of Macbeth’s tyrannical reign offers both relief and moral closure.

- Purpose: Catharsis allows readers to process intense emotions and reflect on the moral lessons of the narrative.

VII. Devices That Create Complexity in the Plot

These tools make stories unpredictable and engaging, often challenging readers to piece together intricate narratives.

1. Flashback

- Definition: A narrative device that takes the reader back in time to provide background information.

- Examples:

- In F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, Nick’s flashbacks reveal Gatsby’s romantic past and his obsession with Daisy.

- In Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman’s flashbacks highlight his regrets and delusions.

- Purpose: Flashbacks add depth and context, enriching the reader’s understanding of characters and events.

2. Red Herring

- Definition: A misleading clue that diverts the audience’s attention from the actual plot development.

- Examples:

- Arthur Conan Doyle’s The Hound of the Baskervilles: The escaped convict is initially suspected of the crime, misleading both characters and readers.

- In Agatha Christie’s mysteries, red herrings often obscure the true culprit.

- Purpose: Keeps readers guessing, adding suspense and intrigue to the narrative.

3. Deus Ex Machina

- Definition: An unexpected or improbable intervention that resolves the story’s conflict.

- Examples:

- Homer’s The Odyssey: Athena’s divine intervention brings peace to Ithaca.

- J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings: The Eagles rescue Frodo and Sam from Mount Doom.

- Purpose: While sometimes controversial, this device can emphasize themes of fate or divine will.

Cultural Influence and Modern Adaptations

Literary devices have evolved across genres and cultures. While metaphors enrich poetic traditions in Eastern literature, symbolism dominates modern Western storytelling. Digital media, like film and video games, increasingly relies on narrative techniques like foreshadowing and imagery to engage global audiences.

Conclusion

Understanding literary devices is crucial for appreciating the artistry in literature. By shaping tone, defining structure, enhancing narrative depth, and deepening themes, these devices enrich both the reader’s experience and the writer’s craft. Explore these devices in classic and contemporary works to see their transformative power in action.

FAQs: Literary Devices Explained

1. What are literary devices, and why are they important?

Literary devices are techniques that enhance storytelling by adding depth, emotion, and meaning. They help writers create engaging narratives and enable readers to analyze and appreciate literature.

2. How to Identify Literary Devices

Recognizing literary devices as a reader is different from intentionally using them as a writer. Often, an author’s application of these tools is subtle—they are felt more than seen.

To address both perspectives:

- For Readers: Examples are provided for each literary device to help you spot them in various texts.

- For Writers: Exercises are included for practising these techniques, enabling you to incorporate them effectively into your work.

3. What Is the Difference Between Literary Devices and Figures of Speech?

While both literary devices and figures of speech enhance writing, they differ in scope and application:

- Literary Devices: These are broader tools that encompass language, structure, style, and narrative techniques used to create specific effects or meanings in a text.

- Figures of Speech: A subset of literary devices, these involve using language figuratively rather than literally. Examples include metaphors, personification, and alliteration.

In essence, all figures of speech are literary devices, but not all literary devices qualify as figures of speech, as the former represents a narrower category.

4. What Is the Difference Between Literary Devices and Rhetorical Devices?

Although literary and rhetorical devices share similarities, they serve distinct purposes:

- Literary Devices: These focus on enhancing the narrative and adding richness to the text. Examples include symbolism, foreshadowing, and narrative voice.

- Rhetorical Devices: These are primarily used for persuasion and influencing emotion. Common examples include hyperbole, rhetorical questions, and appeals to ethos or pathos. They are often found in speeches, advertisements, and debates where the intent is to convince or persuade.

While there is some overlap (e.g., irony can function as both), literary devices typically aim to deepen storytelling, whereas rhetorical devices centre on persuasive communication.